Chess is a global game. Its origins go back to India in perhaps to around the 6th century CE. From there, the game traveled to the Persia, the Arab world, and likely made its way into Western Europe toward the end of the first millennium.

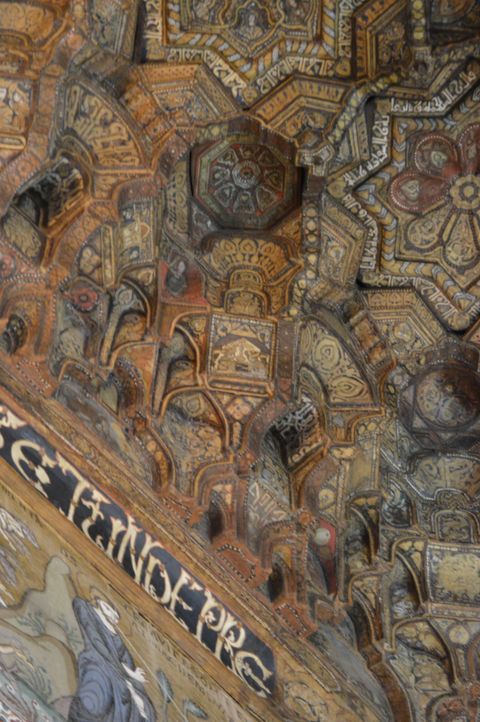

To the right, you can see a portion of the ceiling of the Cappella Palatina, the royal chapel within the Norman Palace of Palermo. that was commissioned by Roger II in the 1130s. The chapel shows a remarkable array of cultural influences, such as Byzantine Greek mosaic work, Latin inscriptions, and Arab architectural features. On the ceiling, the muqarnasat (honeycomb-like vaulting) are adorned with Abbasid-style paintings of a decidedly non-religious nature. One of these paintings, in the center of the image, is considered the oldest artistic representation of the game of chess in the Western world.

But we can take the story a little further back by way of material culture. To the right, you see an image of some pieces of the Charlemagne chess set, housed in the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris. Long held at the Abbey of St. Denis and the subject of the colorful origin story that Harun al-Rashid gifted the set to Charlemagne, the pieces show the seams of the game’s transformation across cultural boundaries: there is still an elephant (not yet a bishop), but there is also a queen (who used to be a vizir in Indian, Persian, and Arab forms of the game). The pieces, incidentally, are now thought to have been made in Salerno (north of Sicily but south of Naples) in the 11th century.

With respect to thinking about the fusing of cultures through games, we might think not only about the game of chess but also about its intersection with the world of medieval mathematics. The mathematical problem of the doubling of the chessboard (what is the numerical result if you put one grain on the first square of the board, 2 on the second, and keep doubling until the last square) has a long-standing medieval history, including its appearance in Occitan lyric poetry. But it also comes up in Leonardo Fibonacci's groundbreaking work Liber abaci

(1202), which introduced the Hindi-Arabic numerical system to the Western world. Fibonacci's work reflects a global perspective; he says that he learned the art of numbers from merchants from Syria, Egypt, Greece, and Provence. Recent scholarship has also suggested that he was using Arabic sources and the 1227 edition of his work, dedicated to Frederick II's preferred scholar Michael Scot, likely benefited from the cross-cultural currents of the Federician court.

Below you'll find a series of textual citations, the first from Fibonacci's work and the next two from medieval Italian poetry that reflects a different kind of game-playing with a distillation of mathematics for a new vernacular audience.

“Indeed it is proposed to sum a sequence of powers of two on chessboard squares using the doubling method, one of which is with a sequence of places with each number the double of its antecedent; with the other a sequence of places with the numbers the sum the preceding doubled places is proposed.”

(Leonardo Fibonacci, Liber abaci 12.9, Sigler trans.)

Se li tormenti a dolor ch’omo ha conti

fossero ‘nsieme tutti ’n uno loco,

ver’ quei ch’io sento, so che parian poco

a quai ne son più canoscenti e conti.

E posso radoppiar scacchieri e punti

e legge farne con ardente foco

bontà di quella che m’ha fatto fioco

[If all the torment and pain that people feel / were gathered together in one place / I know that it would still seem like little compared to what I feel / to those who are wise and true. / and I can double chessboards / and make them seem little by the ardent fire of my pain) / thanks to she who has reduced me to a whisper]

(Onesto da Bologna, Se li tormenti, 1-7)

L’incendio suo seguiva ogne scintilla;

ed eran tante, che ’l numero loro

più che ’l doppiar de li scacchi s’inmilla

[and each spark circled with its flaming ring- / sparks that were even more in number than the sum / one reaches doubling in succession each / square of a chessboard, one to sixty-four]

(Dante, Paradiso 28.91-93)